- Home

- Jane Lebak

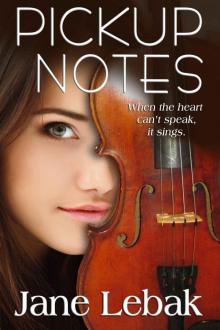

Pickup Notes Page 5

Pickup Notes Read online

Page 5

He checked for oncoming traffic, and when all was clear, he slammed his foot dead to the floor, launching the car to the speed limit and beyond.

I clutched the door handle and shut my eyes.

Josh never noticed when I did that. After years of splitting the cabbie work with his dad, it was instinctual to ignore his passengers, and ignore me he did. He also ignored the laws of physics. We approached escape velocity while ascending the entrance ramp of the Gowanus Expressway, a thousand feet in the sky.

To the driver in front of us, he snarled, “The one on the right! That’s the one that makes it go forward!”

It never did any good to ask Josh to ease up. In the past, he’d taken that as a challenge, and it left me longing for the days my nearly-blind grandfather weaved all over Flatbush Avenue in a Buick the size of a tugboat.

As soon as Josh found room, or maybe even a few seconds before, he cut to the left to pass the guy, immediately forgetting him in order to concentrate on the next car, which by sheer coincidence also went too slowly. “You’d think he’s dragging a couch.” He gripped the wheel, growling, “Hey, guy, I know you’re in a Chrrr-ysler, but it can do better than that.”

A car passed us. Josh muttered, “Mmm-maniac.”

Shooting through the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel, the engine sound screamed off the white tiles like something out of Star Wars. I told myself it would be okay, no really, although I pulled my viola to my chest to shield it with my body. He was a grand-master driver who hadn’t been in an accident in the last three hours. I meant, years. It had been three years since his last fender-bender, and even then he’d been rear-ended.

To his credit, we arrived faster than if I’d taken the train, but I couldn’t kiss the ground because Josh thought that sarcastic.

“I’m nnn-not that bad,” he said as I shut the door.

In the midtown church, a florist’s crew worked at turning the place a violent pink. It was six o’clock. Harrison and Shreya had already arrived.

Harrison glanced up. “You look awful. Did Josh drive?”

“Hah.” Josh set his cello on the floor and removed his jacket. “Really n-n-n-not that bad.”

We stashed our jackets and cases in the sacristy, tuned, and sought out last-minute instructions from the wedding coordinator. The officiant was a young priest whose voice had already softened to a texture I’d transcribe as subito piano, and he paused to admire our instruments.

“Don’t be too pleased with mine,” Harrison told him, frowning at his violin while adjusting the micro tuner on the tailpiece. “The A string keeps going flat.”

I said, “Give it time. It’s cold.”

“It’s had enough time,” he snapped. “Yours isn’t complaining.”

The priest grinned. “Should I pray for it?”

Harrison muttered, “If you think that’ll work better than threats to turn it into toothpicks.”

This was one reason to ride with Josh: heat in the car. Like any piece of wood, string instruments expand and contract, and very few couples get married in a hermetically sealed vault in the heart of a museum. Our best compromise was getting them to room temperature.

Ignoring Harrison’s endless re-tuning, I stood to play a three-octave C scale. At the end, I scanned the frescoed ceilings, listening as the notes died away. “Awesome! These have to be the best acoustics we’ve ever played.”

Harrison looked up. “You and I should get married at Carnegie Hall.”

“Except I’m not marrying you, Harrison.” I projected to test how far it would carry, and sure enough, the wedding coordinator turned from halfway across the church. Every decibel worked for you in this building.

Modern churches annoyed me, with their dead spots where you’d play as loud as you could but no one could hear, where there’d be no air and you had to rearrange the chairs five times to find the spot where you could breathe again. But this one? Gorgeous and functional, like playing inside a musical instrument.

Shreya adjusted her seat, then stepped back to study our placement. “This will do. I guess I can stay.”

I tugged at the edge of her black hair. Our blue-haired beauty once again wore the wig turning herself into a professional, although I guess at some point she’d have to become our magenta-haired beauty. “I’m surprised you showed at all.”

Her eyebrows shot up. “Hey! I wouldn’t skip a performance unless I was bleeding to death!”

I laughed. “Oh, good. I was afraid Harrison’s deal would drive you away.”

More puzzlement. “What deal?”

Harrison looked up from his violin. “Yeah. Um, I didn’t get a chance to talk to her yet…”

Josh stopped tuning. Shreya took a step nearer to us. “What’s going on?”

Harrison looked at me. “Don’t be a coward. You tell her.”

My fearless leader. Fighting a grin, I said, “That bride we booked last Sunday was very...particular...about color coordination.”

Shreya’s eyes flashed. “She wants an all-white quartet, and a brown-skinned Indian woman ruins the decor?”

I smirked. “Oh, far, far better.”

Harrison plucked his A string. “They couldn’t have cared less whether you were white or Indian or Martian. You’re the reason they booked us at all.”

Dead silence. I bit my lip, struggling not to laugh. Shreya looked from me to Harrison, then back to me. “And that’s because—?”

Oh poor Harrison, having to confess. “Because Harrison took note of how particular she was about color coordination and made her a teensie little promise.”

All four of us clustered. My voice wasn’t as steady as I wanted because I was still fighting giggles. “She wants your hair dyed to match the bridesmaid dresses.”

Stepping back, Shreya interrobanged, “What?!”

Josh burst out laughing, and then I was in stitches too. “Oh, it gets better!” I couldn’t help myself. The two violinists were glaring at each other. “Harrison offered it as a perk.”

“She wasn’t going to sign us!” Hands raised, he backed away as Shreya stepped toward him. “I didn’t think you’d mind!”

“You didn’t think I’d mind? And what color is my hair going to be?”

I sing-songed, “Fuchsia!” The acoustics carried it all the way through the church.

Before Shreya could react, Josh muttered, “Thank God it’s not p-paisley.”

I laughed even harder. The wedding coordinator and the priest were staring. Harrison offered a weak smile.

Josh turned to Harrison. “Should I p-paint my cello?”

I said, “How about concert magentas?”

Josh said, “Music printed on p-p-purple paper?”

I looked at him. “We could dye our bow hair too.”

Shreya stood with her eyes closed, but her shoulders shook with helpless laughter. “Fine. Fine.”

Harrison forced a used-car-salesman smile. “See? It’s not so bad.”

“Dude—?” She shot him a look over her shoulder. “It’s called a wig.”

I took my seat, huddling over myself to stifle the persistent giggles while Josh kept shooting me glances that triggered another bout.

I looked up to find Harrison standing over me, and as I was about to make a joke, I stopped. I’d expected his wounded puppy look, but instead—coldness?

Well, he couldn’t fire me right now. Most brides could count to four. “What?”

He murmured, “You enjoyed that far too much,” and before I could respond, he leaned closer. “Don’t do that to me again.”

He turned his back and checked the tuning of his A string.

I hunched over myself, afraid to look in case Josh was staring at me too, or Shreya. I blinked hard, tried to straighten my sheet music only to drop it all. I thrust it back onto the stand, then did scales with my eyes closed, listening to the perfect intonation. C scale. G scale. A-minor scale. It would be okay.

Harrison didn’t say anything else to me. Shreya and Josh had f

allen quiet.

Six-thirty. Our package started with music for the guests half an hour before the wedding, long enough for a Haydn quartet.

Between movements, Harrison adjusted his A string.

“Give it a rest,” Shreya murmured. “It’s good enough.”

“Good enough isn’t perfect.”

Shreya shot back, “Perfect is the enemy of good enough.”

Unsure if Harrison were still pissed, I tested the waters. “What if I garrote you with your own A string? Will that be good enough?”

“Only if it’s in tune when I die.” Harrison plucked the string again, but he didn’t sound angry. “Maybe the bride will be a little late.”

We proceeded to the second movement. As usual before a wedding, they were more interested in catching up than in the musical ambiance. We were background, like the stained glass windows. Musical wallpaper.

By the time we finished the quartet, the priest and groomsmen had gathered at the front (along with, I presumed, the groom). Next, a larger group of guests would fill in during the final five minutes, and then we’d begin. We played a shorter piece.

Seven o’clock. We looked for a signal to seat the families, but none came. After a quick check of the A string, Harrison started the air from Handel’s Water Music.

It ended. Still no signal. Harrison selected another short piece. We played through. Seven fifteen.

My brain itched with a realization: only now had the church begun to fill.

Our contract specified the start time at seven, yet most guests only arrived at seven twenty? Had the bride told us the wrong time? But no, the wedding coordinator had prepped for a seven o’clock wedding, and the groom, who ought to know, had arrived for seven.

Seven thirty. Harrison laid his violin across the seat. “Shreya, take a solo.”

I grabbed the sleeve of his tuxedo with a questioning look.

“I’m talking to the groom. That bride better show up or the check won’t clear the bank.”

I looked down to hide the grin. Only Harrison.

Shreya gave an Irish melody that set the hair on my neck straight up with its subharmonics. Perched at the edge of my chair, I alternated between watching her and watching Harrison conspire with the groom, who then flagged over the best man and the priest. A cell phone came out of the groom’s pocket, and when Harrison returned, Shreya finished up.

So—did we still have a wedding to play? Or were we going to improvise, like the time the bride bolted?

Harrison held up the music for Mozart’s quartet The Hunt.

My eyes widened. A thirty-five minute piece?

Mouth set, he nodded.

Before I could ask whether the bride had fled, the priest took the lectern. “May I have your attention, everyone? We’ve heard from the bride, and she’s running a little late.”

Harrison didn’t appear as unnerved as I by the guests’ knowing laughter.

The priest continued, “While we wait, please relax and listen to the Boroughs String Quartet. We’ll begin as soon as she arrives.”

Harrison leaned close to me. “Quit looking terrified. Hell yeah we’ll give them a concert. At three hundred bucks an hour.”

Well—yes and no. While our contract did stipulate that rate of overtime, who goes to a ceremony mentally geared to play for hours? At a reception we’d at least get a break in the middle. But by forgetting to show up, the bride had us playing indefinitely and, after an unspecified time, needing to sound fresh for the ceremony when everyone (i.e., the check-signers) would be paying attention.

On the other hand, those pink envelopes on my kitchen table would encourage me to make my best effort, so up went the viola, and I awaited Harrison’s cue.

Mozart should have written a longer quartet because he finished before the bride came, so Harrison indicated the Beethoven string quartet that had gotten interrupted at last week’s wedding. Oh, for heaven’s sakes, another thirty minutes? She was an hour late already.

Between two movements, I glanced at the guests expecting to find them mingling, but instead of the sides of their heads I saw faces. Without a wedding to distract them, the guests had begun focusing on the only entertainment in the church. They were staring at me—at us, but at me too. I bet they saw my goosebumps.

Harrison noted the same thing: the faces, the stillness. Between movements two and three, he stood, announced what we were playing (when had he ever done that?), and thanked them for their patience.

And then, ever classy, he reached into the jacket pocket where he kept our CD.

Scrambling up, Shreya grabbed his arm before he could speak.

Silence ruled. It was the longest hour of my life, the moment her dark eyes bored into his hazel ones. Harrison appeared puzzled. Shreya whispered, “Not in a church.”

Defiant, but comprehending he was outgunned, Harrison shrugged, and they both retook their seats.

At eight we sat through another announcement that the bride was finally on her way this time. Beside me, Josh gave a rueful chuckle.

Before the priest stepped down from the lectern, Shreya stood for a solo rendition of “Waiting For A Girl Like You.”

The crowd laughed, and the priest laughed, and Shreya laughed, and I wanted to run. Grab the viola and run as fast as I could.

And then so help me, Shreya gave a recognizable bit of Chicago’s “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” Louder laughter, followed by applause. Someone called, “Can you do ‘It’s Too Late’?” and Shreya obliged.

Harrison’s eyes went as wide as stopwatches. He did the exact opposite of what I wanted to do: he strode to the mike. “I’d like to introduce Shreya Ramachandran, second violinist for the Boroughs String Quartet!”

She stepped out from the chairs as someone shouted “Time In A Bottle—?” and she played thirty seconds of Jim Croce.

Heart pounding, I turned to Josh for reassurance, but given his own wide-eyed stare, I might as well have asked the church mouse. Between this and the “Hotel California,” our reputation was down the toilet. That wedding coordinator would never recommend us again. Once she started chatting up her coordinator friends over margaritas, we’d be forever remembered as that grandstanding quartet who lost their minds.

Shreya worked the crowd. Harrison mentioned our name every single time he could. He introduced me and Josh and even took a couple of digs at the viola. (“You guys have heard violins but not violas, right? That’s because modern recording techniques remove all the extraneous sounds.”)

He urged me to take a solo, but it felt like the floor was made of ball bearings, so he took one himself.

At nine-thirty the wedding coordinator gave a signal that deserved accompaniment by bells like Armistice Day: at last, for real, like seriously, here came the bride. Harrison and Shreya shared the mike as they thanked the guests for their patience.

And then, having already played for three hours, we began the real work.

After the ceremony I was spent like a one-dollar bill. Whenever I moved, pain shot up my left arm and across my shoulders. In a room off to the side of the sanctuary, I rubbed my shoulder, then worked my fingers along my neck. Yehudi Menuhin said a violinist has to be in excellent physical condition because you need to hold your arms above your heart. He didn’t even play the viola, which weighs more, has a heavier bow, and requires more pressure on the fingerboard.

I stopped only when we were approached by a beigeish creature, half sequins and half pearls: the mother of the groom. Oh, good. Payment for the overage.

Then I noted the tightness of her mouth, the steel of her eyes.

Harrison approached the woman, but she refused his handshake. In a thin voice, she said, “We only authorized you to play. No one told you to make a spectacle of yourselves.”

My mouth opened. A spectacle of ourselves? With a bride three hours late to her own event that at its best was little more than pageantry?

Harrison’s eyes widened. “I’m sorry. We made the best of

a bad situation.”

The woman stared down Harrison, then glared at Shreya—who had the flattest expression I’d ever seen—and then gave me a once-over as if I weren’t worth crushing beneath her glittery taupe pumps. I couldn’t breathe.

With the air tinged by the hint of Obsession, she said, “You had no right. None at all.”

An apology lodged in my throat. I couldn’t get it out, but I couldn’t force it down either.

She turned her back to rejoin the bridal party.

Then I realized: all that, and we weren’t even going to get paid?

We four stood in silence for nearly a minute. Finally it was Shreya who broke it. “What crawled up her ass?” She put a hand on Harrison’s shoulder. “At least you got your wish. The violin warmed up.”

“Thanks. Why isn’t the universe listening as closely when I ask for more clients?” He returned to his chair, then wiped down his violin with a cloth to remove four hours of rosin from the belly. “What did she expect? The bride was on California time, but we ruined the wedding?”

“But you know—” and I got up close to Harrison, “they didn’t ask for us to put on a show. When we booked them, we never said we’d start taking requests off pop radio.”

Harrison frowned. “You were onboard with the fusions.”

“They weren’t onboard with the fusions!” Behind me, Josh closed the sacristy door. Good—they’d already heard enough from us. “Bait-and-switch happens to be pretty damned unprofessional!”

Shreya said, “Joey, I was the one—”

“You weren’t the one who grabbed the mike and opened your big mouth!” I didn’t take my eyes off Harrison. “Shreya gave them a snippet. You spun it into a concert the bridal party never intended!”

Harrison folded his arms, one of those poses where you just wanted to hit him because he looked so damn confident. “They never asked for it because they never dreamed the bride would go for an Olympic gold in the fashionably-late competition.”

Behind me, Josh said, “It’s okay. It’s d-d-d-done.”

“It’s not done!” My voice broke. “He screwed us over! We’re not going to get paid because of him!”

Bulletproof Vestments

Bulletproof Vestments The Wrong Enemy

The Wrong Enemy The Boys Upstairs (Father Jay Book 2)

The Boys Upstairs (Father Jay Book 2) Sacred Cups (Seven Archangels Book 2)

Sacred Cups (Seven Archangels Book 2) Bulletproof Vestments: A Father Jay Story

Bulletproof Vestments: A Father Jay Story An Arrow In Flight (Seven Archangels Book 1)

An Arrow In Flight (Seven Archangels Book 1) Upsie-Daisy

Upsie-Daisy Shattered Walls (Seven Archangels Book 3)

Shattered Walls (Seven Archangels Book 3) Pickup Notes

Pickup Notes